Promo: Sex and Sexuality in Tudor England by Carol McGrath

I'm thrilled to share a fascinating article by bestselling historical fiction author, Carol McGrath, linked to her new non-fiction release, Sex and Sexuality in Tudor England. Welcome, Carol!

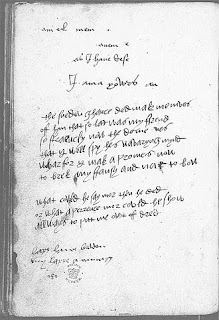

Here, Carol shares details from the Devonshire Manuscript, which tells us about an ill-fated marriage. Read on! It's tragic.

Sex and Sexuality in Tudor England is on my reading list, and I'll review it once I've read it. Make sure to read the other fascinating posts on her blog tour!

The Devonshire Manuscript and Courtly Love

|

| The Devonshire Manuscript |

The Devonshire Manuscript was a volume of poems associated with Surrey’s sister, Mary Howard, whose initials appear on the original binding. Queen Anne’s waiting woman, Madge Shelton, was involved, as was the King’s twenty-year-old niece, Margaret Douglas. There is a joint inscription to Margaret Douglas and Mary Shelton within the book. Poems in this work were scribed by at least twenty different hands. It was passed around Anne Boleyn’s close group, not dissimilar to the way in which we use social media today. They would have been very interesting tweeters. Their verses invited dialogue through which a group of courtly persons wrote to, for and about each in stylised terms.

|

| Margaret Douglas |

These courtiers had access to love poetry by Thomas Wyatt who used sonnet form in his verse and it was Wyatt’s sonnets rather than the popular courtly verse of Geoffrey Chaucer that influenced the manuscript’s verses. Since the book was circulated with blank leaves, recipients conversed with each other using responses, by adding lines and by changing lines. A sentiment expressed in one lyric was answered in another. It returned at intervals to Mary Shelton herself, who would alter any misogynistic lines to pro-feminist ones. Metaphors of courtly love poetry included imprisonment, dying, suffering, accusation, betrayal, concealment, and the notion that one could really die for love.

Henry Surrey is thought to have written the lines, ‘In playful fable each beste can chose his feare.’ His own name even appears in the manuscript. The lines refer to a romance and its unfortunate consequences for a younger step-brother of the Duke of Norfolk, Thomas Howard, who made a private contract of marriage with Margaret Douglas, daughter of King Henry’s sister, Margaret of Scotland. She was a young lady close to the succession. Their situation, a forbidden romance, became one of the Devonshire Manuscript’s focal points. Their love story is a literal illustration of how the tropes of courtly love were evolving and merging with the new sonnet form.

|

| Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey |

Queen Anne Boleyn disapproved of the clandestine relationship between Howard and Douglas, and, since they were part of Queen Anne’s circle, the couple met secretly. An early poem in the manuscript charting the romance says:

Take heed betime lest ye be spied

Your loving eyes ye cannot hide

At last the truth will sure be tried

Therefore take heed.

For some there be of crafty kind,

Though you show no part of your mind,

Surely their eyes cannot be blind.

Therefore take heed.

Some is thought to refer to Anne Boleyn, a warning to be careful to avoid the Queen’s sharp eyes. The likelihood is that the couple would keep a look out until Queen Anne was not in her chambers and they could meet clandestinely. When their secret marriage per verba de presenti occurred, only two persons were party to the secret wedding, Lady Williams and Hastings, a servant to young Thomas’s mother.

|

| Courtly Love |

The situation imploded two months after the execution of Anne Boleyn. The pair were arrested. Margaret’s place in the succession had catapulted her into enormous political importance. That July, two months after Anne’s execution, Eustace Chapuys, the Spanish ambassador, wrote in dispatches, following the arrest of Margaret Douglas that a person of Blood Royal was also to die, but added that for the present this person was pardoned her life considering that sexual intercourse had not taken place. Had it done so she ‘deserved pardon seeing the number of domestic examples she has see.’ Perhaps this comment was Chapuys’s personal dig at the perceived raciness of Anne Boleyn’s court. After all, the Spanish ambassador had no liking for Queen Anne.

Margaret’s relationship with Thomas Howard had unfortunately brought him into the realm of dynastic politics. Their relationship and secret marriage was one that Henry VIII was not prepared to tolerate. England’s revised Treason Act during the 1530s meant that such dalliance was not at all sanctioned, and worse it was regarded as treason. An Act of Attainder on 18 July 1536 affected both Margaret Douglas and Thomas Howard, causing them to be placed in the Tower (the Act forbade the marriage of any member of the king’s family without the king’s permission). Whilst imprisoned in the Tower, the romantic couple continued to write courtly poems which were later slipped into the manuscript. It is impossible to prove conclusively that Thomas wrote the prison poems later placed in the collection because there is a lack of attested example of his handwriting. His authorship cannot be disproved either. Margaret, lucky for her, was treated leniently. She fell ill and was moved to Syon Abbey under the supervision of Syon’s abbess. She was released on 27th October 1537. Thomas, under sentence of death, was spared execution. He remained in the Tower, where he died on 31 October 1537.

Many poems contained within this manuscript refer to the plight of imprisoned lovers who are unjustly torn apart. These are poignant love poems such as:

For term of life thy gift you have

Thus now adieu my own sweet wife

From TH which no light doth crave

But you the stay of all my life.

Was TH young Thomas Howard? Did he write these lines? Paranoia and surveillance were a primary component of King Henry’s court. Yet, courtiers involved in the writings in the Devonshire Manuscript were just as blindly self-involved as the youth of any generation since can be. Their poems were a vehicle for the most interesting of youthful preoccupations – their own personal social dramas and their own coded and secret messages scribed in lyrics. This manuscript is a captivating glimpse into the youthful aspect of Henrician courtly society.

~~~

Blurb:

The Tudor period has long gripped our imaginations. Because we have consumed so many costume dramas on TV and film, read so many histories, factual or romanticised, we think we know how this society operated. We know they ‘did’ romance but how did they do sex?

In this affectionate, informative and fascinating look at sex and sexuality in Tudor times, author Carol McGrath peeks beneath the bedsheets of late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century England to offer a genuine understanding of the romantic and sexual habits of our Tudor ancestors. Find out the truth about ‘swiving’, ‘bawds’, ‘shaking the sheets’ and ‘the deed of darkness'. Discover the infamous indiscretions and scandals, feast day rituals, the Southwark Stews, and even city streets whose names indicated their use for sexual pleasure. Explore Tudor fashion: the codpiece, slashed hose and doublets, women’s layered dressing with partlets, overgowns and stomachers laced tightly in place.

What was the Church view on morality, witchcraft and the female body? On which days could married couples indulge in sex and why? How were same sex relationships perceived? How common was adultery? How did they deal with contraception and how did Tudors attempt to cure venereal disease? And how did people bend and ignore all these rules?

~~~

About the Author:

Carol McGrath

Following a first degree in English and History, Carol McGrath completed an MA in Creative Writing from The Seamus Heaney Centre, Queens University Belfast, followed by an MPhil in English from University of London.

The Handfasted Wife, first in a trilogy about the royal women of 1066 was shortlisted for the RoNAS in 2014. The Swan-Daughter and The Betrothed Sister complete this highly acclaimed trilogy. Mistress Cromwell, a best-selling historical novel about Elizabeth Cromwell, wife of Henry VIII’s statesman, Thomas Cromwell, was republished by Headline in 2020. The Silken Rose, first in a Medieval She-Wolf Queens Trilogy, featuring Alienor of Provence, saw publication in April 2020. This was followed by The Damask Rose. The Stone Rose will be published April 2022.

Carol is writing Historical non-fiction as well as fiction. Sex and Sexuality in Tudor England will be published in February 2022. Carol speaks at events and conferences and was the co-ordinator of the Historical Novels’ Society Conference, Oxford in September 2016. She is an avid reader and reviews for the Historical Novel Society and is a member of both the Romantic Novelists’ Association and Historical Writers Association. Carol lives in Oxfordshire with her husband.

Find Carol on her website: www.carolcmcgrath.co.uk

Follow her on Amazon: @CarolMcGrath

Subscribe to her newsletter via her website (drop down on the Home Page).

Comments

Post a Comment